Why Most African American Descendants of Slaves Trace Their Roots to Inland Regions, Not Just West Africa's Coast

When discussing the transatlantic slave trade, much of the focus tends to be on the coastal regions of West Africa—places like Ghana, Benin, Togo, and Ivory Coast. These were indeed major ports of departure for millions of enslaved Africans. However, many African American descendants of enslaved people today trace their ancestral roots not to the coasts themselves, but to the inland regions farther north of these coastal nations.

Inland Origins, Coastal Departure

The misconception that most enslaved Africans originated from coastal areas stems from a misunderstanding of how the transatlantic slave trade operated. European slave traders rarely ventured deep into the African interior. Instead, they relied heavily on established African trade networks, empires, and middlemen to supply enslaved people—many of whom came from regions hundreds of miles inland.

Major inland ethnic groups such as the Mande, Hausa, Fulani, Yoruba (inland before they migrated southward), and others lived in the savannah and Sahel zones, north of today’s coastal countries. These populations were frequently caught up in internal wars, state rivalries, and slave raids that fed the demand from coastal traders and European buyers.

For example:

The Asante Empire (inland Ghana) and the Dahomey Kingdom (inland Benin) conducted large-scale slave raids into neighboring territories.

Muslim states in the Sahel, such as the Sokoto Caliphate or Kong Empire, captured and sold non-Muslim captives into slavery.

Inland trade routes extended from the heart of West Africa (Mali, Burkina Faso, northern Nigeria) to the coast, where captives were sold to European traders.

Coastal Ports Were Just the Last Stop

The coastal forts and trading posts—Elmina (Ghana), Ouidah (Benin), and others—served as export hubs, not points of origin. By the time enslaved Africans reached these ports, they had often endured long forced marches from the interior. This means that although they left from the coasts, their cultural, ethnic, and linguistic roots were tied to inland societies.

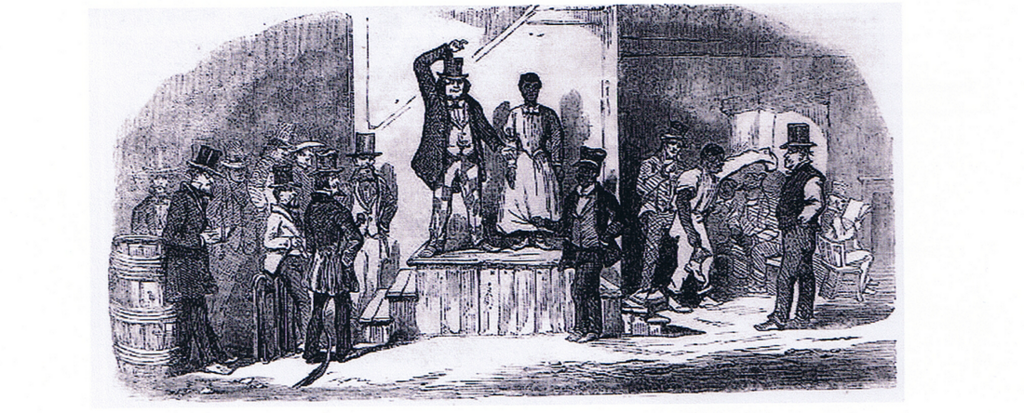

Black Friday! Another batch of slaves traded!

The Legacy in the Americas

This inland origin is reflected in the African American cultural legacy. Many African American linguistic patterns, religious traditions (like those tied to Yoruba or Mande spiritual systems), and genetic markers point to Central and Northern West African origins.

In short, while the transatlantic slave trade’s visible traces—forts, castles, ports—remain on Africa’s coast, the human origins of the enslaved often lie much deeper inland. Recognizing this helps us better understand the complex web of African history and the true roots of African American ancestry.

For guided visits and cultural experiences of Northern Ghana, see also various tour offers, below: