The Inland Slave Routes of Ghana: A Journey Through Shadows

Ghana’s inland slave routes were the arteries of a brutal trade, stretching from the northern savannah to the coastal forts. These paths carried thousands of enslaved Africans through camps like Pikworo and Salaga, shaping a legacy of pain, resilience, and historical reckoning.

Long before the infamous dungeons of Cape Coast and Elmina became symbols of the transatlantic slave trade, the suffering began deep inland. Across Ghana’s northern and central regions, a network of inland slave routes connected remote villages, slave camps, and market towns to the coast — forming a hidden geography of captivity and commerce.

Mapping the Routes of Captivity

The inland slave routes were not single paths but interconnected corridors, shaped by terrain, tribal alliances, and colonial interests. Captives were often taken from areas in present-day Burkina Faso, Niger, and northern Ghana, then marched south through towns like:

- Pikworo (Nania): A slave transit camp where captives were held, fed from stone troughs, and auctioned.

- Salaga: Known as the “slave market of the north,” Salaga was a major hub where enslaved people were sold to coastal traders.

- Kete-Krachi: A key waypoint along the Volta River, used for transporting captives by canoe toward the coast.

- Assin Manso: The final inland stop before reaching the castles, where captives bathed in the “Last Bath” river before entering the dungeons.

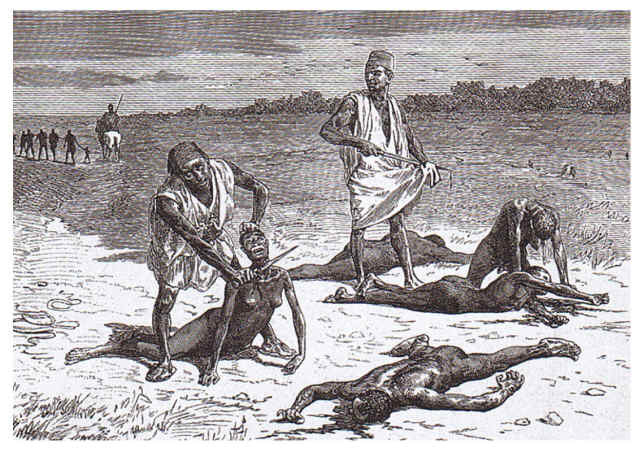

These routes were often hundreds of kilometers long, and captives were forced to walk barefoot, chained together, with little food or rest. Many died along the way — from exhaustion, disease, or abuse.

Not strong enough, to be sold? This is, what happened! This is work of African slave hunters!

Trade and Power

The routes were sustained by a complex web of local kingdoms, middlemen, and European traders. Empires like the Ashanti and Gonja played dual roles — sometimes resisting the trade, but often participating for economic gain. The Ashanti, for example, became a major supplier of captives, using the routes to transport war prisoners and enslaved people to Salaga and beyond.

European powers — Dutch, British, Portuguese — rarely ventured inland. Instead, they relied on African intermediaries to capture, transport, and deliver enslaved people to the coast. This decentralized system made the trade efficient, brutal, and difficult to disrupt.

Sites of Memory

Today, remnants of these routes still exist — in stone carvings, oral histories, and sacred rivers. Places like Pikworo and Assin Manso have been preserved as heritage sites, offering visitors a chance to walk the paths once trodden by chained feet. The Volta River, once a watery highway for slave transport, now flows quietly, bearing witness to a forgotten past.

Local communities continue to honor the memory of those who suffered. Annual rituals, storytelling, and educational programs aim to keep the history alive — not to glorify it, but to ensure it is never repeated.

Why It Matters

Understanding Ghana’s inland slave routes is essential to grasping the full scope of the transatlantic slave trade. These paths were not just logistical — they were psychological corridors of trauma, separating people from their homes, families, and identities.

They also reveal the complexity of African involvement — not just as victims, but as participants, resisters, and survivors. Reckoning with this history allows for healing, dialogue, and a deeper connection to the ancestral journey.

For guided visits and cultural experiences of Northern Ghana, see also various tour offers, below: